Detailed Exam reviews and Questions asked in SBI PO Prelims on April 29 – Slot 3 (2 pm to 3 pm)

Want to Become a Bank, Central / State Govt Officer in 2020?

Join the Most awarded Coaching Institute & Get your Dream Job

Now Prepare for Bank, SSC Exams from Home. Join Online Coure @ lowest fee

Lifetime validity Bank Exam Coaching | Bank PO / Clerk Coaching | Bank SO Exam Coaching | All-in-One SSC Exam Coaching | RRB Railway Exam Coaching | TNPSC Exam Coaching | KPSC Exam Coaching

Detailed Exam reviews and Questions asked in SBI PO Prelims Slot 3 (2 pm to 3 pm)

Dear Aspirants,

Questions asked in Aptitude:

Approximation questions – 5

Number Series – 5

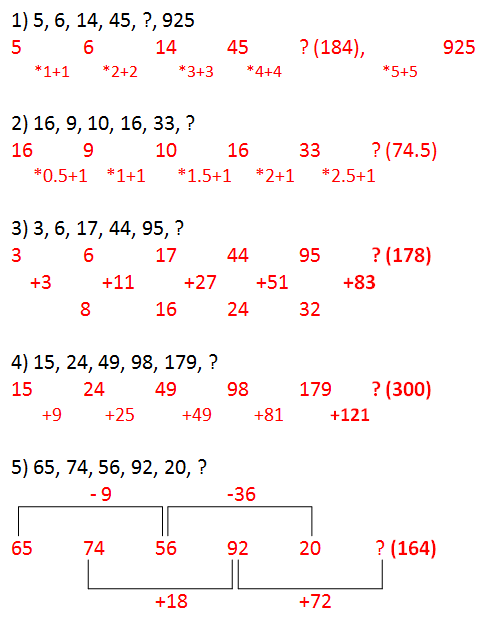

Questions asked in Number Series

Quadratic Equations – 5

Application Sums – 10 (From Time and Work, Partnership,Average, Profit and Loss, Boats and Streams, SI )

DI (Line and Table) – 10

Level of Questions – Moderate

Good Attempts- 20 to 25

Questions asked in English:

Cloze Test like word substitution based on New Pattern- 10 questions

Comprehension based on Internet Technology and Computer – 10 questions

Questions asked in Comprehension: Courtesy: Mr.Kavikumaran

Why everything is hackable – Computer security is broken from top to bottom

OVER a couple of days in February, hundreds of thousands of point-of-sale printers in restaurants around the world began behaving strangely. Some churned out bizarre pictures of computers and giant robots signed, “with love from the hacker God himself”. Some informed their owners that, “YOUR PRINTER HAS BEEN PWND’D”. Some told them, “For the love of God, please close this port”. When the hacker God gave an interview to Motherboard, a technology website, he claimed to be a British secondary-school pupil by the name of “Stackoverflowin”. Annoyed by the parlous state of computer security, he had, he claimed, decided to perform a public service by demonstrating just how easy it was to seize control.

Not all hackers are so public-spirited, and 2016 was a bonanza for those who are not. In February of that year cyber-crooks stole $81m directly from the central bank of Bangladesh—and would have got away with more were it not for a crucial typo. In August America’s National Security Agency (NSA) saw its own hacking tools leaked all over the internet by a group calling themselves the Shadow Brokers. (The CIA suffered a similar indignity this March.) In October a piece of software called Mirai was used to flood Dyn, an internet infrastructure company, with so much meaningless traffic that websites such as Twitter and Reddit were made inaccessible to many users. And the hacking of the Democratic National Committee’s e-mail servers and the subsequent leaking of embarrassing communications seems to have been part of an attempt to influence the outcome of the American elections.

Away from matters of great scale and grand strategy, most hacking is either show-off vandalism or simply criminal. It is also increasingly easy. Obscure forums oil the trade in stolen credit-card details, sold in batches of thousands at a time. Data-dealers hawk “exploits”: flaws in code that allow malicious attackers to subvert systems. You can also buy “ransomware”, with which to encrypt photos and documents on victims’ computers before charging them for the key that will unscramble the data. So sophisticated are these facilitating markets that coding skills are now entirely optional. Botnets—flocks of compromised computers created by software like Mirai, which can then be used to flood websites with traffic, knocking them offline until a ransom is paid—can be rented by the hour. Just like a legitimate business, the bot-herders will, for a few dollars extra, provide technical support if anything goes wrong.

The total cost of all this hacking is anyone’s guess (most small attacks, and many big ones, go unreported). But all agree it is likely to rise, because the scope for malice is about to expand remarkably. “We are building a world-sized robot,” says Bruce Schneier, a security analyst, in the shape of the “Internet of Things”. The IoT is a buzz-phrase used to describe the computerisation of everything from cars and electricity meters to children’s toys, medical devices and light bulbs. In 2015 a group of computer-security researchers demonstrated that it was possible to take remote control of certain Jeep cars. When the Mirai malware is used to build a botnet it seeks out devices such as video recorders and webcams; the botnet for fridges is just around the corner.

Not OK, computer

“The default assumption is that everything is vulnerable,” says Robert Watson, a computer scientist at the University of Cambridge. The reasons for this run deep. The vulnerabilities of computers stem from the basics of information technology, the culture of software development, the breakneck pace of online business growth, the economic incentives faced by computer firms and the divided interests of governments. The rising damage caused by computer insecurity is, however, beginning to spur companies, academics and governments into action.

Modern computer chips are typically designed by one company, manufactured by another and then mounted on circuit boards built by third parties next to other chips from yet more firms. A further firm writes the lowest-level software necessary for the computer to function at all. The operating system that lets the machine run particular programs comes from someone else. The programs themselves from someone else again. A mistake at any stage, or in the links between any two stages, can leave the entire system faulty—or vulnerable to attack.

It is not always easy to tell the difference. Peter Singer, a fellow at New America, a think-tank, tells the story of a manufacturing defect discovered in 2011 in some of the transistors which made up a chip used on American naval helicopters. Had the bug gone unspotted, it would have stopped those helicopters firing their missiles. The chips in question were, like most chips, made in China. The navy eventually concluded that the defect had been an accident, but not without giving serious thought to the idea it had been deliberate.

Most hackers lack the resources to mess around with chip design and manufacture. But they do not need them. Software offers opportunities for subversion in profusion. In 2015 Rachel Potvin, an engineer at Google, said that the company as a whole managed around 2bn lines of code across its various products. Those programs, in turn, must run on operating systems that are themselves ever more complicated. Linux, a widely used operating system, clocked in at 20.3m lines in 2015. The latest version of Microsoft’s Windows operating system is thought to be around 50m lines long. Android, the most popular smartphone operating system, is 12m.

Synonyms and Antonyms – 2 to 3 questions

Phrase replacement based Spotting Error – 10 questions

Level of Questions- Easy to Moderate

Good Attempts – 11 to 16

Questions asked in Logical Reasoning:

Puzzle Test – 4 set – 20 questions

(i) 8 persons with Ages – 5 questions

(ii) 6 persons based puzzle – 5 questions

(iii) Ranking based puzzle

MOT – 5 questions

Misc – Ranking – 1, Blood Relation – 1, Direction Test – 2 , Coding and Decoding – 1 – over all 5 questions

Level of Questions- Moderate (Time Consuming in Puzzle)

Good Attempts- 12 to 18

7 comments

Reasoning part (puzzles) are really time consuming so while attending reasoning keep an eye on timing…. Other than puzzles other question in this part was easy….

Does d same english questions appeared n all d slots??

No, Its a collective Review

sir answer for 2 question in series is 83.5

sir, answer for 2 question in series is 83.5

To crack English section in SBI PO just read all articles in http://www.economist.com (science and technology). Its verified and 3 slots RC picked here ly..

To crack English section in SBI PO 2017 just read all articles in http://www.economist.com(Science and Technology). Its verified and 3 slots RC picked here only..